As I mentioned in a recent post that focused specifically on retellings of Norse mythology, the whole “Viking thing” (or “Northern thing,” as W.H. Auden more accurately put it) is presently riding a big wave of popularity. Prominent television shows, movies, books, video games, and music albums engage with these themes, characters, and settings in one capacity or another. The inspirations for these works range from historical reality to legendary history to folklore and mythology. With such an array of sources feeding into this creative output, one might wonder: how do the actual sagas themselves fit into it all?

And that’s a bit of a loaded question. While most people are familiar with the term “saga,” it’s not always clear what exactly we mean when we use it. It’s original usage in Old Norse indicated a sort of oral-telling about the given subject. In the present-day Scandinavian languages, “saga” simply means “story,” while in present-day English, the word implies something epic—a story that spans multiple generations. And the sagas do span multiple generations; read one and you’ll have the pleasure of learning all manner of intricate details about the main characters’ various forebears. Scholars classify the sagas into a handful of categories, ranging from the highly fantastical and often mythological Legendary Sagas to the violent and generally reliable Contemporary Sagas. The common thread through all the categories is that the sagas are prose works written in the Middle Ages by Scandinavians, usually Icelanders.

This article is concerned with the categories of the Kings’ Sagas and the Sagas of the Icelanders (which include the Vinland Sagas). Together, the sagas in these two categories tell of the rise and rule of royal power in Norway, the settlement of and conflicts on Iceland, and the explorations to Greenland and North America, known as Vinland. These sagas feature less of the fantastical than do the Legendary Sagas or myths, but elements of magic, witches, and draugar (Norse undead) nonetheless abound. These are the sagas to which the term is most often applied in the broader, undefined sense, and the following are five worthwhile novels directly inspired by those tales.

Vinland by George MacKay Brown

Vinland is a historical fiction novel that draws heavily on the Icelandic Vinland Sagas (The Saga of the Greenlanders and The Saga of Erik the Red), about Leif Eriksson’s voyage to Vinland, and Orkneyinga Saga, about the Norse settlement of and conflicts over the Orkney Islands. The book follows the life of Ranald, who inadvertently joins Leif Eriksson’s voyage to Vinland, and eventually visits Norway and partakes in the Battle of Clontarf—the major battle in Ireland in which Brian Boru led his men to victory over the invading Northmen. Most of the book takes place on Orkney itself and progresses via Brown’s immersive prose, focusing on Ranald’s desire for peace as the violent struggle for power in Orkney escalates around him.

Styrbiorn the Strong by E.R. Eddison

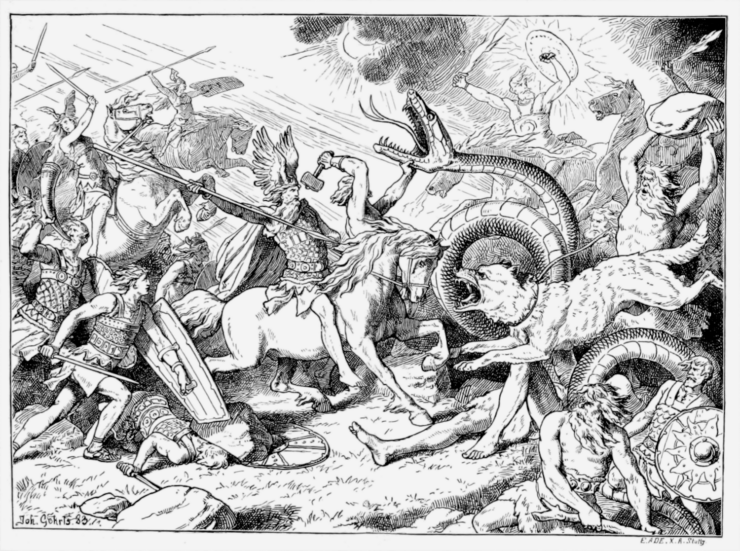

Originally released in 1926, Styrbiorn the Strong is E.R. Eddison’s attempt to recreate a long-lost saga about the eponymous hero. The figure of Styrbiorn appears in a number of old sources, including Heimskringla, a compendium of Kings’ Sagas written by Snorri Sturluson in the 13th century, and Flateyjarbók, Iceland’s largest medieval manuscript. In these old sources, Styrbiorn is presented as a legitimate claimant to the Swedish throne and leader of the fabled warrior brotherhood known as the Jomsvikings (who also have a saga of their own, and have been featured recently in Netflix’s Vikings: Valhalla fantasy television series).

Eddison, whose work was praised by J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, and Ursula K. Le Guin, weaves a highly compelling tale that follows the adventurous course of Styrbiorn’s life to his final encounter with his uncle, Eric the Victorious, at the fabled Battle of Fyrisvellir. While drawing on the old sources, Eddison’s prose is of its era, which means that the novel is written in a much more verbose and highly dramatic (some might even say overwrought) manner than is found in the sagas themselves, or in more recent novels, for that matter. If such epic prose is your to your liking, then H. Rider Haggard’s Eric Brighteyes might also be of interest. Released in 1891, it is written in a similarly verbose style and features an original plot focused on a love triangle inspired by the mythological Saga of the Volsungs.

Saga: A Novel of Medieval Iceland by Jeff Janoda

Saga: A Novel of Medieval Iceland is a novelization of a short segment of Eyrbyggja Saga, an Icelandic saga set in the northwestern part of the country that is well-known for its abundance of characters who return from the dead to haunt the living. The book specifically focuses on chapters 30 to 38 of the original saga (as delineated in the Hermann Pálsson/Paul Edward translation published by Penguin)—it takes 20 pages from the saga translation’s original 140 pages and expands them into a full 350 page-long historical fiction novel. The subject matter is as quintessential to an Icelandic saga as it can get: a dispute over land ownership that spirals out of control into an increasingly violent feud. With its standard novel format and rich but straightforward modern prose, Saga: A Novel of Medieval Iceland is the easiest-to-get-into book on this list.

The Ice-Shirt by William T. Vollmann

The Ice-Shirt by William T. Vollmann is the closest thing to an actual saga on this list: it spans many generations and is intermittently told in a manner reminiscent of the sagas themselves, employing curt and to-the-point prose. Presented as a modern compendium of some very old sources, the story begins in Norway, extends across the Atlantic via Iceland and Greenland, and eventually arrives in North America. The Ice-Shirt draws heavily on Heimskringla and the Vinland Sagas, weaving the events and characters from those ancient sources together with Norse and Inuit mythological elements into an original tale. The book is the first in Vollmann’s expansive Seven Dreams series, which focuses on conflict between Europeans and Native Americans over the ages.

Nutcase by Tony Williams

Tony Williams’ Nutcase is a retelling of The Saga of Grettir the Strong, an Icelandic saga about the eponymous anti-hero who spends most of his life as an outlaw. While Nutcase follows the same essential plot as the Icelandic original, Williams has transposed the story from the stark, natural landscape of medieval Iceland to a decrepit, brutalist housing estate in present-day northern England. Told in an almost stream-of-consciousness manner and relying heavily on British slang, the result is an incredibly fresh and wild ride as well as the most original interpretation of an Icelandic saga on this list. Over the course of the novel, we follow the life of Aidan Wilson (as Grettir is renamed in the book) from his youth as an unruly lad to his stint as a local hero for having vanquished a very creepy, draugr-inspired villain, then on to his decline as an inebriated outcast and his inevitable, ultra-violent showdown with the long arm of law.

Rowdy Geirsson is the author of The Scandinavian Aggressors and translator of The Impudent Edda. His writing has appeared in McSweeney’s, Metal Sucks, Scandinavian Review, the Sons of Norway’s Viking Magazine, and is forthcoming in Medieval World: Culture and Conflict. He can be found skulking in the abyss at Twitter (@RGeirsson), Instagram (@rowdygeirsson), and Bluesky (@rgeirsson).

Oh I will have to read that one by Eddison, how I LOVED The Worm Ouroboros…

Is Poul Anderson’s Hrolf Kraki’s Saga too on the nose for this list?

The late, much lamented Michael Scott Rohan’s Winter of the World sequence that starts with The Anvil of Ice, is perhaps the most entirely realized Norse mythos / saga-inspired fantasy work (IMHO). Well worth reading if you haven’t.

@2,

This could be Five Novels Written by Poul Anderson…..

Need to mention The Long Ships by Frans G. Bengtsson. I went into it with no expectations and it’s now one of my favorite books of all time.

I didn’t know people still read George MacKay Brown!

Actually, I’ve never read Vinland, either, but there was a time I read his poems over and over.

For another saga-type work, Jane Smiley’s <i>The Greenlanders</i> is set in Greenland (well, yeah) during the 14th and 15th centuries and written in the style of the Icelandic community sagas. Bleak and beautiful. Come to think of it, it would also fit on the “reading for a time of climate change and long defeat” post.

The Jomsvikings play a prominent role in these books too, which make up The Bold One Saga.

Cherezińska, Elżbieta; trans. by Maya Zakrzewska-Pim. The Widow Queen (2022) and The Last Crown (2023).

Highly recommended for those of us who have loved such novels set in Europe’s North and East, after the end of the western Roman Empire, and in the early medieval era — you know you are one of those if you loved Nicola Griffith’s Hild, or Cornwell’s Saxon Chronicles.

Here we have the intersection of the beginning of Poland as a state, Bohemia, the Rus, Kiev, Hungary, Denmark, Norway, Sweden and England, paganism and Christianity, all connected via the family of and the figure, Queen Swietoslawa

I have to put in another plug here for Winter’s Daughter: The Saying of Signe Ragnhilds-Datter by Charles Whitmore, which is written in much the way an Icelandic saga would be if updated to current English usage. In other words the style is not archaic or flowery or overwrought, but the story is all about the characters’ actions not their thoughts or recollections (so no interior monologues or flashbacks). Despite the postapocalyptic setting, the story of woman whose violent life and journeys from Scandinavia to Africa and North America and back to the north would feel very familiar to an old Norse skald.

Joan Clark’s Eiriksdottir (1994) is a retelling of part of The Saga of Eirik the Red, with his daughter as the protagonist.

No love for Lloyd? I know, I know, they’re technically children’s books, but The Chronicles of Prydain by Lloyd Alecander are so good.

@10 They’re excellent but not at all Norse, so don’t belong here. Their inspirations are entirely Welsh.

Worth adding Tolmie’s All the Horses of Iceland to this list. Great short atmospheric travel tale of someone from Iceland who goes on an increasingly long trip and comes back with high quality horses. Author has a splendid sense of setting.

I was returning to mention All the Horses of Iceland, which arrived here this afternoon. I had no idea how small a book it was though … barely 100 pp.

Glen Cook’s Dread Empire books have several stories that are set in a North that is clearly inspired by the sagas.

Count me in on the Greenlanders. It captures the tone of the sagas beautifully. I started on sagas when I was in grade school with juvenile versions of Njal’s Saga and Egil’s Saga. Nearly 70 years later I haven’t lost interest.

FWIW, I got about a third of the way through the Janoda book. It didn’t hold my interest although it had the dry tone down well.

What about Harry Harrison’s The Technicolor Time Machine? A.k.a. The Time-Machined Saga. There’s a decent summary at Wikipedia. Read it when it was serialized in Analog many years ago. Great fun.

There’s also David Drake’s Northworld trilogy, from 1990 or so.

@17

That’s based on the Eddas, not the Kings’ or Icelanders’ sagas

@16

Speaking of Harrison, The Hammer and the Cross series gets pretty deep into the Viking stuff, although it’s not directly based on any sagas.

@8–Another vote for Winter’s Daughter, if only for the name ‘Stephen the Nearly Lucky” which fit him soooo well.

At the risk of violating norms of self-promotion, there is a new book that falls into this category.

“Neal’s Story” is a re-setting of “Njal’s Saga” into a fictional version of the American Old West.

Sort of off- or on-topic: has anyone come across a good “file the serial numbers” off version of the Norse in Greenland in a future setting within the Solar System? Anderson did one about a human interstellar colony that failed, but I can’t think of one set in a relativistic universe. Combine the history of the Greenland Norse settlements (absent any non-settler locals) with a “Dairien Scheme” analogue of stupidly self-delusional capitalism (which seems appropriately apt these days) in a realistic Solar System (Venture Capital City, Mars) and someone could get a pretty good cautionary tale out of it.

Also – Space Viking by Beam Piper. ;)

@21 – If you’re thinking of Anderson’s story “The Alien Enemy”, that was set in an Einsteinian universe.

@16/Ivan Van Laningham – I really enjoyed the Technicolor Time Machine, but I felt terrible for the archaeologist